Main navigation - Library

Secondary Menu - Library

Secondary menu

Search suggestions update instantly to match the search query.

Discovering Google’s hidden databases

Introduction

It is widely understood that Google crawls the web and has negotiated permissions with most data providers to index their web content, including the content within some subscription databases, on the understanding that subscription content will not be shared with unsubscribed users. What is less obvious is that Google operates a series of discrete and separate search tools that operate on specific subsets of all the content and datasets Google has harvested and that each provide specific functionality not available from the Google Web search. Once included to some extent in what Google once called “universal search”, these are now almost entirely relegated to their individual database silos. The scope and utility of these more specific databases – some widely known, others much less so – is reviewed below.

Expert Google Web Search tips

You can download cheat sheets detailing search tips for Google Web Search from Karen Blakeman's business website, RBA Information Services.

General notes on Google search

Google Web search has a broader and different set of search commands than most of the other more specific Google databases (with the notable exception of the Google Patents database).

As with most web information, the display of search results now follows ‘mobile first’ design principles. This means in practice that information is hidden behind buttons/links, only 100-150 search results are available (making the total number of search results even less meaningful than it was before), search results are geared towards commercial uses and so academic search can only be uncovered using more expert search techniques and the use of Google’s more specific databases/tools.

If you are looking for a specific article, document or report using a Google search where you know the document name it can still be difficult to find because Google changes the title it lists for some documents in its search results to one that it’s machine learning algorithm believes better reflects the content of the document. This means that some documents appear under a different title in Google search results.

Different Google databases use different lists of commands, most being more restricted than Google Web search.

The “not quite hidden” databases

Above the search results for a Google Web search, a series of what appear to be search filters are listed, including News, Maps, Images, Videos, Shopping, Books, Flights, etc. The list varies somewhat, depending on the search that was run. Many of these are actually separate databases/tools that offer unique functionality not found in the Google Web search, operating effectively as web-based versions of the various Google mobile apps.

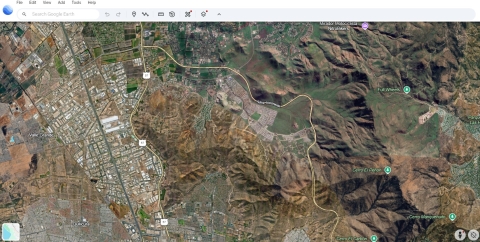

Maps – Similar to the Google Maps mobile app, the map view can be changed to highlight everything from reported Covid-19 densities and road traffic congestion to transit maps at the click of an on-screen button. This service brings together many separate datasets and displays them visually as map overlays. Includes surprisingly accurate transport timetables and directions, often better than those provided by local bus companies, etc., themselves.

Videos – Different to YouTube, being more news focused. For video searches, YouTube (also owned by Google) is recommended instead because its Advanced Search offers a much wider choice of filters.

Flights – useful for identifying alternative airlines and routes, particularly if you are exploring travel options to/from obscure and hard to reach destinations. Uses ITA software to process data from the same global distribution services as flight comparison sites. The main differences are that none of the search results in Google Flights appear appear at the head of the search results because they have been sponsored by an airline or other company, the order of results being purely determined by Google’s ranking algorithm, which attempts to put first the cheapest, fastest and most direct flights.

Finance – Inferior in almost every way to Yahoo! Finance. Makes it easy to search for a company and see a chart tracking its recent stock prices. This database has lost much of its former functionality, including spreadsheet downloads of historical data. Prices are updated with only a 20 minute delay behind markets but historic data does not make clear whether prices for any given stock on any given day were the opening, closing or average prices, severely limiting its utility.

Country localisations

The content presented in versions of Google localised for different countries are so different that it is like searching an entirely different database. Searching different countries’ localised versions of Google is therefore useful to obtain a breadth of different perspectives on world news or to research a person, company, sector, event, etc. that took place in another country.

It is no longer sufficient to visit the web address for another country’s Google, e.g. www.google.fr for the French localisation of a Google search. Google now detects your British IP address and proceeds to localise your search results for you in the UK, despite your best efforts. Four methods currently exist to achieve a different country localisation of Google search results:

- Use a VPN (other than the University VPN) to display an IP address in the country whose localised Google results you wish to view. This is the simplest and most effective method but is very often impossible because use of a private VPN is not possible on the University network.

- Add a country localisation command to your search, e.g. site:ac.fr. Be aware that this command will exclude all relevant results from other countries that might have appeared in the search results had you used any of the other methods.

- Click on Search Settings > Advanced Search. Beneath all the other options, under “Then narrow your search results by…”, select the country (and/or language) for your results.

- Run the search as normal, and then to the end of the search results URL add: &cr=countryxx where ‘xx’ = 2-letter country code for the desired country of localisation.

If advising clients, method 3 above is probably the most straightforward to explain.

Google Books

When first launched, Google was eager to digitise as many different publications as possible in their entirety in order to provide their machine learning algorithms with a sufficiently large corpus of material for them to become fine-tuned. Google Books therefore contains many full-text works of a diverse range of historic materials up until the 1970-80s, including books, magazines, and (mostly US) newspapers. This sometimes means that it is useful for finding the full text of some older books. Google Books is currently undergoing a rolling interface update, with more modern content being presented with a much more streamlined interface than older content.

Google Books is a useful database to find articles, advertisements, newsletters (particularly academic newsletters) and newspaper articles on particular events and companies. It is possible to build up an outline picture and timeline for how a company represented itself and its products over time or even to explore academic newsletter reporting of interviews surrounding the Chenobyl disaster, for example, using Google Books searches limited to “magazines”.

Google Books now operates a fuzzy search, intelligently finding alternative search terms in materials. For example, a search for medical negligence will retrieve results matching either “medical negligence” or “clinical negligence”, etc.

Some Google Web commands (notably including the before: and after: date limiter commands do not work in a Google Books search. It is easier to click the Tools button and use the web form provided under Advanced Search. This allows a reliable ISBN/ISSN search, ebooks and “full view only” filters for search results and enables a publication date range search.

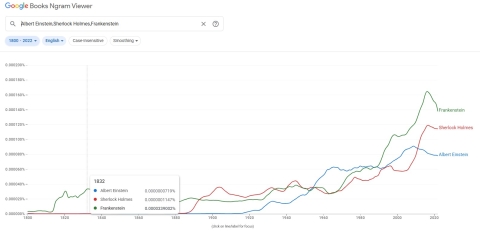

Ngram viewer

Graphically represents the relative frequency of words/phrases entered in the search box in the Google Books over time database. Separate each different term to be compared simultaneously in your search with a comma. Coverage now extends up until 2019.

You can move from the Ngram viewer to see the results in Google Books matching a specific search term for a particular date range, making this a powerful search tool. It also allows you to identify upticks and sudden drop-offs in usage, helping to target other searches.

Google Scholar

Google Scholar has been found to comprise a wider coverage of scholarly articles in foreign languages than either Scopus or Web of Science. It is less accurate than these other services, however, because it ignores publishers’ metadata.*

An entirely separate database from Google Web search, Google Scholar indexes the content of articles within subscription databases and so includes a level of indexing not available in Google Web Search.

Unlike Google Web search, Google Scholar almost never includes alternative terms in its search results, nor does it drop search terms. Most searches are carried out similarly to ‘verbatim’ web searches.

While Google Web search is limited to 32 search terms, Google Scholar imposes a 256 character limit on search strings, including operators (such as OR) and spaces. It also uses a different, more limited, search syntax to the Google Web search.

* When it was first set up, Google Scholar was expected to be a short-lived project. Publishers offered access to their metadata but Google declined because they wanted to develop machine learning algorithms capable of efficiently recognising elements such as creator names and publication dates from their expected position in predictably structured documents. This is how Google Scholar extracts its indexing terms to this day.

Google Scholar search syntax

Google Scholar does not search for alternative terms, and while use of the Boolean OR operator seems to work in some cases, cursory testing suggests that running separate searches for alternative terms returns a larger number of more reliable results.

Google Scholar’s Advanced Search search commands are limited to:

intitle:

author:

site: (note that this finds the hosting site, not the author’s affiliation!)

source:

For date limiters, it is necessary to limit the search to the search boxes in the Advanced Search screen or to use the date slider to the left on the search results screen. The before: and after: commands do not work in Google Scholar.

Pre-prints in Google Scholar

Pre-prints are a treacherous minefield in academic research. Frequently updated and eventually published, ensuring you are using the most recent version of a manuscript is not always easy. The first search result should be the most recent version but any variation in title, the author names listed, the order or authors, etc. will cause Google Scholar to create a new, separate search result for the new version. This often happens when a pre-print is finally published in a journal. It is therefore important to check alternative search results that might be for the same manuscript/article and to click on the “x published versions” link and follow the link to the hosting site to check whether a new version has been published but not yet fully indexed by Google Scholar.

Alternatives to Google Scholar

The open access directory Core and the academic search engine BASE, together with the Core and Unpaywall browser plugins are useful and free alternatives to Google Scholar, particularly useful for finding pre- and post-prints.

Google Patents

Google Patents is often more up to date than subscription patent databases and patent searching experts habitually use both in tandem. It also boasts by far the most sophisticated suite of search commands of any of Google’s databases, including many proximity limiter terms that were dropped from the Web search years ago. It is also possible to search for chemical formulae using a variety of naming and structural search conventions.

Patent searching is a highly specialised endeavour, since patents are written in the most general way possible to anticipate as many competitor claims as possible, while the patent classification systems of different countries also vary widely and are not always followed perfectly. Librarians are therefore strongly advised not to carry out any patent searches for clients but to refer them to specialists in patent searching. Within the University, this means referring them to the Research and Innovation Department.

Google Datasets Search

Google Datasets Search appears poised to replace the Google Public Data Explorer, since the Public Data Explorer has shrunk in recent years and now carries a link inviting users to use the Datasets Search for more datasets.

A useful tool for finding data repositories, including the existence of paid-for/firewall bounded repositories. Results often link to articles in Google Scholar that have cited the dataset.

Caution

If more than one dataset source is listed, take great care which you choose. Often only one dataset is the original and others are copies of the dataset. It is also necessary to check that the dataset is the latest version and has not subsequently been withdrawn following questions over its validity.

Search syntax

The site: limiter command only works for full domains, i.e. you can limit your search results to site:port.ac.uk but not to site:ac.uk.

Search results may be filtered by their last updated date, format, broad topic area, and usage rights. Unfortunately, selecting “non-commercial usage permitted” appears to be inconsistent/unreliable, often returning no results even when it is known that at least one large open source dataset matching a search is publicly available.

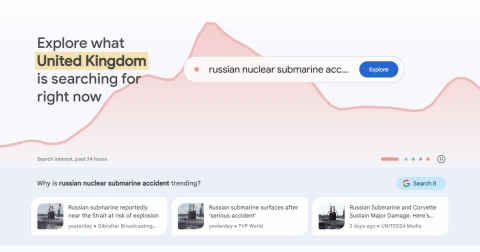

Google Trends

Originally a tool developed to assist website developers with metadata/search engine optimisation, Google Trends shows the relative (%) frequency of one or more search terms, separated by commas, in searches across a specified timeframe. Useful for monitoring interest in different things, such as products, people, companies, innovations, etc., over time. Results can be restricted to specific cities/countries/geographic regions and subject areas (“topics”).

It is possible to see “related queries” and use these to run date-limited Google Web and Google Books searches to investigate trends further, for example to investigate what news/events preceded/contributed gave birth to a trend or sudden increase in interest and awareness in a person or brand.

Constitute

Not a formal Google product, the Constitute Project is supported by Google Ideas.

Comprises a database of English translations of the constitutions (or the nearest available equivalents, such as Magna Carta for the UK) for all the world’s countries, overlaid with a very simple search interface. The search is tool is very basic and lacks all the sophisticated search tools usually associated with Google Web search.

The Data Stories tab offers a growing collection of articles exploring themes and ideas with a constitutional theme built using Google datasets, including explorations of constitutional matters and conflicts.

How rapidly this database is updated following constitutional changes is uncertain.

Google Arts and Culture

Google Arts and Culture includes galleries, artists, stories, images of paintings, museum artefacts, and a fascinating ‘colour explorer’ tool that enables users to select colours from any image in the database or from a digital image they upload and find other images that share its colour palette, optionally filtered by the addition of one or more simple search terms. This provides a wealth of design ideas and creative inspiration and can be used to find artworks that share a colour palette with an organisation’s brand colour palette.

Clearly copyright is of concern when using such images. An alternative that searches only Creative Commons licensed content on Flickr is TinEye’s Multicolr search tool. This search tool is even more sophisticated than Google’s Arts and Culture database, allowing users to choose up to five colours from an image and further specify the proportions these colours should appear in related images.