Main navigation - Library

Secondary Menu - Library

Secondary menu

Search suggestions update instantly to match the search query.

The windmills in your mind

Reflection for reflective writing and lifelong learning

Welcome to a mind-expanding trip down the rabbit hole into the wonderful world of reflective writing, as I try to answer the age old question, “So what really did just happen?” Be prepared for this to go from the mundane to the surreal and back again. Reflection tends to be like that – you feel like your mind is about to come apart at the seams, only for everything to come into clearer focus than before.

Understanding your process

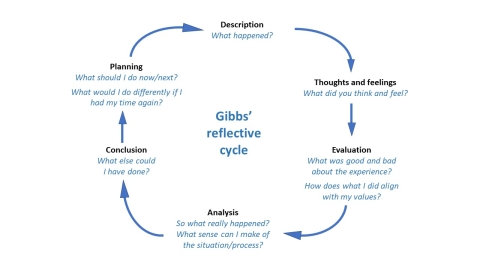

In study and work, reflection often appears under its pseudonym, “evaluation”. Both words mean to look back over what has passed, to identify what was valuable and what was unhelpful, and to consider how you might do things differently in the future to get a better result more easily. For projects and essays where you are asked to reflect on your work, various thinkers have worked out a series of useful steps to get you started, which are summarised in what has become known as Gibbs’ learning cycle or Gibbs’ reflective cycle:

We are encouraged to think about events, feelings, what was valuable and what was frustrating. It is here that reflection gets deep. Once you start picking apart what you/everyone in a group did/did not do, how well that worked, or didn’t, and how all of these things made you feel, you may find that you discover new layers to the puzzle. It can feel like peeling an onion, as you discover subtle nuances in the situation that were not obvious before you started. Working your way onwards and inwards, you find that your thoughts, actions and feelings interacted. Which was driving your actions – what you thought or what felt most comfortable at the time? Why did that feel comfortable – were you attracted to a familiar way or working or avoiding something that worried you? Was it the best way? How did things turn out?

This process is always set out by lecturers to sound clear and systematic, logical and absolute. In my experience, it feels much more like that described in this hypnotically esoteric song by Noel Harrison.

Onwards and inwards

You may well come around to questioning your original statements about what happened as your understanding gets deeper. You might decide that the way your group mates felt about one another before the project started might have had a bigger effect on how you all approached the project than anything else, or it might be that a pivotal idea came up and was ignored or seized upon and that this led to conflict or success. My point is that you do not know where reflection will take you when you start out.

It is a journey into your past and the unknown as you explore the individual facts you already know but have yet to connect and form into a meaningful, self-consistent picture. You must be brave enough to be completely honest about what was happening. Always ask whether the picture you are forming makes sense. If it doesn’t feel right, something is missing or being misrepresented – something else was going on instead or as well. Given how many ways you can recreate the past from a few remembered memories and facts, your feelings are most likely to be the things that guide you in putting together an accurate picture. What feels ‘right’ generally is.

Once you are done with the seemingly endless cycle of revisiting and analysing facts, feelings, and recollections, you can decide what lessons you have learned that can be generalised to what you do in the future. The ways we decide to change after consciously reflecting on past experiences are what help us develop and increase our capability over time as scholars and professionals.

Going ever deeper

There are layers to reflective learning, and the depth to which you are comfortable going to explore both your motivations and approaches will largely determine how much you learn from your experience. The deeper you look, the better you will understand your approach and why it is performing as it does, and the more nuanced your understanding of what might need to change to deliver the impact you want to see.

Looking deeply is a phrase often used by the late mindfulness expert Ven. Thich Nath Hahn, who advocated looking again and again at things that seemed intractible until we can understand why the motivations and factors involved reveal themselves and we can identify with and appreciate the position of everyone involved. The layers of reflection are typically represented as loops, each circling back to look again, more deeply, at the reasons why something has happened. In the following examples, I outline the three loops of reflective learning from a group perspective, but they apply just as well to you and your individual process.

Single loop learning

Asks is everything going well, if not what shall we change? Assumptions and goals go unchallenged, just changing course to reach the same goal, like travelling down the same river in the same boat but deciding between oars and sail power.

Double loop learning

Questions the underlying assumptions and approaches that guide actions. Why are we doing what we are doing?

Triple loop learning

Questions the fundamentals on which strategy rests - who are we, what do we value, should we even be doing this, and if so, are we approaching this in the right way (for us, to attain what we want in the way that satisfies our values)?

Lifelong learning

Finally, you might remember we called this a ‘cycle’ earlier. The process never ends because once you have changed how you work based on what you learned from what you did before, you will start applying it to what you do next and then repeat the cycle, reflecting on that and improving, refining and enhancing your understanding of what works and what doesn’t under different circumstances. You will discover that you do not have to wait until something is over before reflecting on it. You may find that reflection eventually becomes a habit of mind, a process that continually ticks over as you work, as you question why you are doing things the way you are and if there might be a better way. Eventually, you will develop a highly nuanced and sophisticated understanding of how to get things done, which will help make you successful in whatever you choose to do in life.